introduction

Although I grew up in a small Devon coastal resort, the youngest of three, Dartmoor has fascinated me for as long as I can remember. As a child it meant special days out, inevitably ending in cream teas at Widecombe. There were trips to Dartmeet and Becky Falls, where the rocks in midstream were never quite large enough to keep us out of the water. Then one day our feet remained dry and as a reward we were allowed to climb Hey Tor, providing we all stood well back from its cliff-like edges. From the summit there are extensive views of many moorland hills and now, over forty years on, I have climbed them all.

Anyone who is familiar with Dartmoor literature will instantly recognise the debt I owe to various authors. It is both amusing and remarkable how often some stories are repeated, in various versions, by different writers. Folk tales, such as "Salting Down Father" and some historical events like the potato market are often told. In general, references are given in the text below where one writer is the main or sole source. For those wishing to read more, there are four works that I regard as indispensable: W. Crossing, A Guide To Dartmoor and E. Hemery, High Dartmoor Land and People, both topographical guides; R. H. Worth, Dartmoor, for an overview of archaeology; and lastly L. A. Harvey and D. St Leger-Gordon, Dartmoor, for natural history.

The original inspiration for these photographs was T. A. Falcon's Dartmoor Illustrated, published in 1900. I have had enormous fun hunting down all the sites he visited and this present selection, like his, is a tour around some of the scenery and history of the open moors, starting at Widecombe. One major objective has been to allocate a similar number of pictures to each quarter; a list of all the places visited with their map references is in the back. Many of the sites involve walking more than a mile from the nearest road (or 1.609km for those imperially challenged; I am unashamedly old-fashioned and all my walking is done with feet that move by inches and know when they have been for miles!). The open moor possesses many tracks and paths though only some, like those within the Okehampton artillery range and one between Nun's Cross and Eylesbarrow, are maintained in any systematic way. Most of the others are overgrown, not always well defined and sometimes even discontinuous, so tracing their routes can be difficult. I have found a large-scale map the next best thing to a comfortable pair of walking boots. Ordnance Survey, "OS" in the text, make an excellent 1:25000 version in their Outdoor Leisure series: for now one map-printed on both sides - conveniently covers all the moorland, but it is a devil to handle on a proper Dartmoor windy day!

Place names cause a particular difficulty. On my bookshelf there is a small collection of Dartmoor tomes, well over a yard long, and they frequently squabble over spellings. It is no wonder, for presumably many were directly first transcribed from local dialect, which does not always sound like the written word. One notorious example is the way "Teign" can be pronounced. I went to school in Teignmouth and heard both "Tin" and "Teen"; but "Tyne" and "Tayne" are also sometimes used. The spellings given here are those that most books agree on: they are not necessarily right, so all bets are very firmly hedged and where necessary I have given the OS version as well.

Dartmoor is a National Park which, in the fashion of the day, means it comes complete with a Park Authority. This is not a local council but a committee, funded by both Devonshire ratepayers and national taxpayers, with a membership drawn only partly from local councils within the Park. They are responsible for all planning decisions and also have powers to regulate recreational activities, which includes the suspension of public access to open moorland, in the interests of conservation. One notable feature of their present activities is in the considerable reduction of car parking spaces, usually done by banking up the roadside verges. They mean to prevent casual car parking, aiming to control erosion ; but what they actually achieve is an increased roadkill tally, particularly of sheep. On fine autumn evenings these find tarmac warmer than the nearby grass and so lie upon a road the motorist cannot now leave.

In reality the Park Authority can only have a limited role in the conservation of moorland flora and fauna. It is practically badly handicapped because it has no direct jurisdiction over sheep and cattle grazing, which currently have by far the greatest and most widespread impact on moorland wildlife and habitats. Farm stock levels are primarily determined by "Rights of Common" that are contingent on property, which is generally held within the modern National Park. These rights are based on various practices considered to have arisen "time out of mind" and the people who hold them are known as "Commoners". They are regulated by another statutory committee, one on which the Commoners themselves enjoy a permanent overwhelming majority, which thus ensures that their interests are very well protected.

The Act which set up this Commoners Council was sponsored by the Park Authority itself. In 1987 Elizabeth Prince wrote "one measure of [its] success will be when observers of livestock on the moor . . . will have no cause to complain", in Prince E and Head J, 1987; Dartmoor Seasons, page 117. This book was produced in association with and copyrighted by the Dartmoor National Park Authority. Yet animal welfare cases still continue: in September 2001 one Widecombe farmer was fined £9750 for causing his livestock unnecessary suffering: Dartmoor Magazine 2001; no 65 page 7. To make an impact on stock levels the Park Authority has had to adopt some indirect method of control; in designating ESAs - Environmentally Sensitive Areas - it might have the very mechanism it requires.

Yet back door methods are at best blunt instruments: there are naturally grumbles that box ticking and number crunching has replaced common sense. Alas, politicians and their bureaucrat lackies ever have been thus. Cecil Torr lived near Lustleigh and kept a diary, in which he noted a 1918 order for increased corn production. The target was for 30% and "I supposed the fools imagined that an average of 30% on all farms was the same thing as 30% on every single farm." Needless to say everyone was made to plant up 30% of their land with corn, regardless of the suitability of their land for growing grain, in Torr C, 1970; Small Talk at Wreyland, book II page 55, a condensed version, published by Adams and Dart. Traditionally livestock was not overwintered on open moorland, being returned to the in-bye every autumn; but the modern practice is to depasture both sheep and cattle all year round, a regime that will not easily preserve the fragile upland ecology. Bracken, one major bane of upland pastures, is fast increasing and heather just as fast decreasing. The practice of burning selected areas has most likely accelerated this change: called "swaling" on Dartmoor, it aims to make a patchwork of pastures, each one at a different stage in its growth cycle. It is a practice that comes from northern grouse moors.

Regularly carried out each spring, this burning does no harm to bracken rhizomes, which are all still safely dormant underground. All the old dry growth and any ungerminated seeds are burned; the result is often patches of bare earth that persist until autumn. Worse still, newly burnt areas are never fenced and are immediately grazed, with stock left to browse all re-growing shoots as well as the few seedlings which do appear ; but bracken, being poisonous to animals, is left untouched and takes full advantage of the opportunity to compete for scarce nutrients in the moorland soil.

Old photographs show a lushness of vegetation and a diversity of habitats that have now been much reduced by overgrazing. An example of what might be can presently be seen at Meldon. The new reservoir was ring-fenced in the mid 1970's and excluding all stock has allowed gorse, heather, whortleberry and a good many sapling trees to flourish; there is now a narrow band of vigorous new growth next to the water's edge. Outside the fence it looks as if it is just grass, for everything else is eaten so flat it most likely will not flower. Without flowers there will be no seed and so no regeneration: when the old plants die there will be no young ones to replace them. On nearby Longstone Hill grazing is so intense there are even patches of bare soil on its summit. Yet at least by keeping hillsides bare overgrazing has given access to large areas of moor that would otherwise be most difficult to walk.

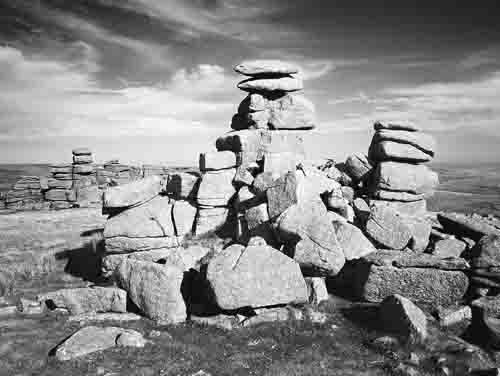

Much of the open moorland is just that: an exposed, wet and windswept plateau that is layered by history. The remains of most ages - together with their industries - are often well represented. It is humbling to find prehistoric monuments and think their stones were set precisely so, perhaps four thousand years ago. Dartmoor was then well populated and has many archaeological sites, with stone rows a particular speciality. A good example of Bronze Age settlement can be found around Kes Tor, SX665863, where there are foundations of circular dwellings, fossilised field walls or reaves and on Shuggledown nearby, stone rows, burial sites and traces of a stone circle.

When the climate changed from warm to cold and peat began accumulating, the upland was abandoned. Although it would be surprising if after the Bronze Age ended there was no metal extraction at all, apart from a few possible locations, no obvious Iron Age settlements, like Chysauster in Cornwall, have been found. Not until the Middle Ages was there again recognisable colonization; but at this time the major endeavour belongs to tinners, who by pick and shovel re-shaped whole hillsides and made kings rich, through taxation levied on the metal they produced. Last to radically alter Dartmoor was Essex Man, in the shape of a Georgian landholder called Tyrwhitt. He attempted cultivation and enclosed large areas of open pasture, but despite such efforts Dartmoor was not made profitable and he lost a lot of money. Stock that is left out all year has to be hardy and is now mainly of Scottish origin, being blackface sheep and galloway cattle, first introduced towards the end of the nineteenth century. Their high numbers are due not to lush pastures, but to large State subsidies, without which their keep would not be viable.

Farm subsidies changed on 1st January 2005, from payments made for production to payments based more upon land areas. How this will affect current stock levels on Dartmoor remains to be seen. One retired commoner from near Scorhill, talking in July 2005, considered the impact would be dramatic. There were signs of less stock around Teign-e-ver, but in general levels that autumn did not look much different, at least on the western side of Dartmoor. The moorland hills are not civilized grasslands for Devon's watershed lies here, separated into two distinct areas: one lies north and the other south of the road between Moretonhampstead and Tavistock. Each area has at its heart a blanket bog of wet and spongy peat morass. To cross them on foot precipitates a hopping match with every tussock, where each misjudged landing is rewarded by a knee-high squirt of thick, black ooze. Such places are generally best avoided.

High up the East Dart one day, on the lower slopes of Cut Hill, I met a family of two children and their mother, who was wet and grimy to her waist. "I took a wrong turning" she explained, "and nearly lost my boots!" Not all damp hazards are confined to large bogs: most valleys contain small pockets of liquid sludge that lurk beneath a firm peat topping. They are completely hidden under a covering of innocent-looking surface vegetation : their only warning is when an unwary heavy tread finds the ground quite literally shaking underfoot. Locally these hazards are called "featherbeds" or "quakers".

Off the moorland there is a network of pretty, yet narrow lanes, most of them running below banks of earth faced with massive boulders. Many are beneath the ground level of surrounding fields, having started their life as simple ditches that separated neighbouring estates. Some are so narrow they are barely one car-width wide; driving through them is always nerve-wracking, specially where the last obvious passing place was at least two tight zig-zag corners back. Nor is that the only problem: as anybody who has relied on Devon signposts knows, they often manage to list any place but the next, so arrival at the chosen spot is only guaranteed if it has been passed at least twice, preferably from opposite directions. My map-reading skills have been hard won, born of too many wrong turns round the next blind corner. This approach of trial-and- error has its compensations though: each river makes a scenic exit from the moors and I have seen them all.

Each year the number of visitors to the Park increases. So if you look at the pictures here collected and wonder where all the people are, the answer is they aren't. Many years ago a straw poll showed that of all those who came into the National Park by car, only one in ten walked further than a hundred yards. Certainly it is true that some attractions are heavily visited and have been so for a century or more; but they are few in number and are either a well-known Dartmoor treat like Hey Tor, or right beside the road like the Plym round Cadover Bridge. Even today it is surprising how few visitors walk any distance, even on summer bank-holiday weekends; perhaps something here presented will show them what lies beyond their car park.

A word of caution, however: for some decades now a large part of northern Dartmoor has been used for military training, sometimes using live munitions. Those pictures that were taken inside the training ranges have all been marked with an asterisk; access is permitted, but only when there is no live firing. Details of fortnightly military schedules are given by a telephone answering service on Okehampton (01837) 52939. The boundary of each range - there are three - is given on the ground by a series of marker poles painted red and white. Once these are crossed, metal objects must on no account be touched: they might be dangerous and can explode if they are moved. Though I personally have seen nothing nastier than spent rifle bullet cases and the occasional water-bottle, people have been injured and some killed, so please be very careful.