south-west dartmoor

RIVER DART

The tumbling waters of East and West Dart come together at Dartmeet, at a place just below the present road bridge. Not far upstream is a single arch, all that remains of a once substantial clapper bridge. It is contemporary with that of Postbridge and like it served a track which was replaced by the turnpike road. A flood in 1826 threw the imposts down and it was then partially restored: in Falcon's book there is a picture of it standing "with a gap on the western side", Falcon T A, 1900; Dartmoor Illustrated, page xxv and plate 51. This is a popular watering-hole, always well patronized throughout the year. Today it has a car park, ice-cream kiosk, tea shop and toilets: facilities that are all very welcome on a fine summer's day.

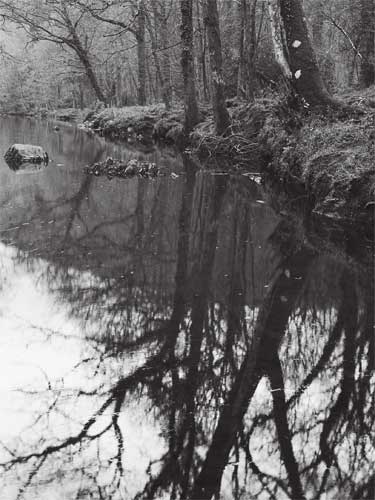

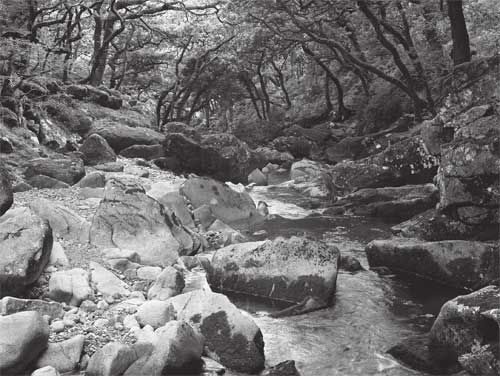

Downstream from Dartmeet the valley is deep and in places precipitous, thickly wooded and very beautiful. A path runs along the left bank, winding up and down slopes strewn with scree. It is well-defined as far as Eagle Rock, but becomes much more difficult to follow afterwards. The trees next to the river are mostly oak and are beginning to resemble those of Wistman's Wood, but as yet look neither so old nor so gnarled. Between them are glimpses of the river, which now has islands and deep pools with a procession of spectacular rapids. In a little under five miles the path ends at New Bridge, SX712709. The trees continue downriver until the lovely woods of Hembury, just north of Buckfast. They are owned by the National Trust, who allow access along various well-made paths, one of which runs alongside the western river bank, where it overlooks a series of deep pools. These seem tranquil enough, but all have fast currents swirling beneath their glassy surfaces. Above the river a long, stiff climb leads to prehistoric remains on the hill-top. They are mostly Iron Age, with a Mediaeval motte-and-bailey in the middle: the Neolithic causewayed camp of Hembury is in a different place, next to the A373 between Broadhembury and Payhembury, well to the east of Dartmoor.

In contrast to the areas around Crockern and Two Bridges that were enclosed by the Improvers, the better land at Dartmeet had already been settled many centuries earlier. One such place is Rowbrook Farm with its small cultivated fields of bright green pasture. It lies in a small, almost hanging valley sheltered by surrounding gorse and bracken covered hills. The first documentary evidence of farming here comes at the end of the thirteenth century, but much of the area had been enclosed before, in the Bronze Age. Immediately west is Vag Hill, which has an extensive set of reaves, or prehistoric land divisions, that are recognisable to this day as a pattern of low stone banks which enclose rectangular areas. All the reaves are set out in long, straight parallel lines that cover the gentler slopes of the hill top, but there are no traces of them now in the cultivated fields of Rowbrook itself.

Down below Rowbrook at the bottom of the Dart valley, beside a watery meadow is the tor OS calls "Luckey" ; the riverside end is sometimes referred to as Eagle Rock. It is famous not for the eagles - more likely to be ravens or choughs - which used to nest here, but for the activities of pixies luring the unfortunate to their doom. One such was a stockman working for Rowbrook Farm. Jan Coo was a former workhouse boy, now grown to a young man; over many evenings he had heard his name being called from the river. At first cautious, he went searching only when in the company of other farm workers, but they never found anybody. Finally, the calls became too seductive and he rushed down to the river alone, naturally never to be seen again. One route he might have taken is the path from Rowbrook's fields that leads directly past Eagle Rock.

The farm fields are isolated by moorland. Ranged around are Sharp, Mil and Hockinston Tors. The scenery across the Dart is so spectacular that one local worthy, Dr. Blackall, built a carriageway beside them so he could enjoy the view as he rode past. The trees behind Dartmeet Clapper belong to the ancient tenement of Brimpts and were felled some years after this photograph was taken. Since Falcon's day trees have nearly shut in Eagle Rock, shrinking the water meadow to a small area around Row Brook, the little stream that gives its name to the farm above.

RIVER AVON

A lane from South Brent goes north-westwards along the pretty River Avon to Shipley Bridge, where there is a car park next to the ruins of a factory that once made naphtha out of peat. The lane then turns almost due east, climbing out of the valley to Yalland Cross; but a private Water Company service road continues on beside the river for about two miles, as far as a small reservoir called Avon Dam. Pedestrian access is allowed and it is a very popular walk. Less than half a mile upstream the river is confined in a miniature gorge, bubbling over an assortment of rock ledges, cascades and rapids. The Rhododendron ponticum growing by the riverbank were deliberately planted by the owners of Brent Moor House, which stood below Black Tor. Its foundations are under fir trees and covered in moss, beside the Water Company's road.

Some distance above the reservoir, where the streams of River Avon and Western Wella Brook meet stands Huntingdon Cross. It was set up after the dissolution of the monasteries as a boundary marker for Brent parish and not as a way-post for the path OS calls "Abbot's Way". Certainly there was an early route through here, but it was more probably connected with the mediaeval wool trade rather than with any monastery. Like other long disused moorland paths, this one has stretches that are well defined, but it also has a nasty habit of disappearing round the next bend.

Just past the cross it fades completely and here I once met a walker from the North Country. He lamented that in Lakeland marks made on maps had real meaning at ground level, whereas on Dartmoor they were much more of a cartographer's fancy. Considering the OS references to abbots his arguments sounded most seductive! A short wall has now been rebuilt behind the cross, blocking the neck of land at the confluence of Avon and Western Wella. I was told this was done at the behest of the farmer: he wished to prevent others' stock straying onto the Duchy land he leased; but the local bullock population was taking no notice whatsoever. They were quite happily fording the streams on either side.

Not far upstream along the Avon from Huntingdon Cross there is a small clapper of two openings. It is off the beaten track in a picturesque setting; looking south from it on the horizon are Grippers Hill and then Bishops Meads, which is crossed by OS Abbot's Way. In the middle distance are the slopes of Huntingdon Hill, which is a place full of history. There is a prominent ancient burial site on top, the Heap O'Sinners. Mediaeval tin streaming and a later tinning mill are on its western side, together with a rabbit warren which started early in the nineteenth century, with artificial burys built in groups; they look exactly like cemeteries made of freshly minted Bronze Age barrows. To see all this the shortest route - though not perhaps the least hilly - lies along Huntingdon Mine track from OS Lud Gate, SX684673. Once the col between Pupers and Hickaton is reached, a stiff uphill slog, the track across Pupers Plain is good walking, with fine views towards the green warren fields. The warrener's house has, like many of its contemporaries, been razed to ground level: a chesnut tree now marks its approximate location.

The warren lands once extended both sides of the Avon, connected by a clapper bridge. This was built by a warrener sometime in the early nineteenth century, a much later date than OS Gothic lettering implies. Groove marks left by tare-and-feather, a distinctive modern way of cutting granite, are plainly visible in the horizontal slabs. By the early 1990s there had been considerable erosion where the Avon cut away its western bank and isolated the clapper impost. The Park Authority rebuilt this section of the bank in 1998 and perhaps they did their repairs too well; a wet millennium winter washed all out in a flood on December 31. There has been a restoration and one may once again cross dry-footed, but sadly all is not as it was, for the far horizontal slab in the picture above has been replaced the wrong way round, with its bankside end now resting on the central support.

On Huntingdon, rushes mark many of the warren burys; looking south the Avon snakes down to meet Avon Dam with its reservoir, a patch of grey-blue amongst greens. This is almost identical to E. H. Ware's picture, plate 8 in Harvey L A and St Leger-Gordon D, 1953; Dartmoor, where it is reproduced in colour. Sadly, the rich heathers he pictured on Bishop's Meads have now gone, victim no doubt to both overgrazing and swaling.

HOLNE RIDGE

West of the River Dart lies Holne Ridge, with its flanks pock-marked in various places by opencast tin working. Ringleshutes is one of them, worth visiting for some fine views across south-east Dartmoor, extending all the way from Fernworthy's firs to tors above Widecombe. The area can easily be reached from Combestone Tor, SX670718, where there is a small car park: climb the eastern side of the pretty O Brook past Horn's Cross until some outlying gerts are reached, almost due south. The main workings, including the remains of mine buildings, lie east along the ridge, just below the Sandy Way, a track that connects the mine with Michelcombe, SX 695688.

Another mining area can be found about a mile to the north-west. Hexworthy mine, Called Hooten Wheals by OS, like so many other moorland ventures has had a chequered career. Originally starting out as Mediæval streamworkings beside the O Brook, its lodes were sporadically reworked many times, probably in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries as well as the nineteenth. Its later history is punctuated by heavy investment for a few years of production. The last cycle started in 1905 when a new electric mill was built ; but in 1914 mining stopped altogether. Scattered around are all the tell-tale signs of these mining endeavours. A massive wheel-pit lies next to the mine's track. Below the mill's stamping floors, where ore was smashed to pieces by heavy hammers, are remains of circular buddles, used for a washing process that separated the denser pure tin particles from ordinary rock. However, these ruins are not simply the result of neglect and weather: they were initially produced by gunnery practice during World War II. Many bullet holes are plainly visible in what remains of the original plasterwork on buildings that scatter the O Brook's valley sides.Much of the wall in the picture above has now sadly collapsed.

A monks' path is generally supposed to have run across Holne Ridge between the abbeys of Buckfast and Buckland. There were already routes along the valleys, one of which went past Dartmeet, but using them could prove difficult in prolonged wet weather. Walking higher up on drier hillsides would certainly have been quicker and all along the hillside there is a line of crosses, each one in sight of the next and all may be markers for the fabled "Abbot's Way". The last in line is aptly called Mount Misery, for on the western flank of Ter Hill it is on a hillside open to every north wind that blows. Lying prone in 1878, the socket stone had been cut to a depth of a mere five inches. It was reset, but by 1879 had fallen again. Remaining fallen until the Dartmoor Preservation Society had it restored in 1885, when their Hon. Secretary, Mr. Tanner and a certain Mr. W. Crossing supervised its cementing back in place.

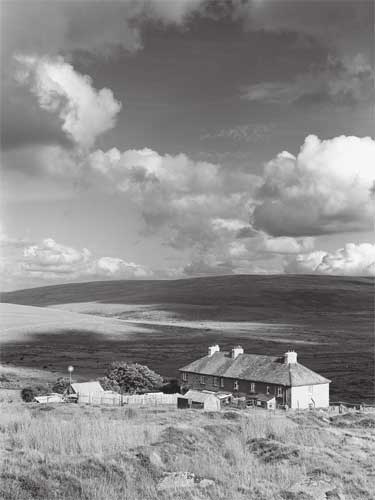

IMPROVERS' HOLDINGS

Downhill from Mount Misery lie the ruins of an Improver's endeavour. Built in 1812 by a Mr Windeatt, Fox Tor farm's main claim to fame is the unfortunate pillaging of Childe's Tomb. The story of Childe is a cornerstone of Dartmoor's mythology: a Saxon nobleman, he was caught in a winter storm near Foxtor Mire, which he could not pass. Lost and finally exhausted, he slew his horse, disembowelled it and crept inside for shelter. Before succumbing to the cold, he wrote a will leaving his lands to whoever gave him a Christian burial. The monks of Tavistock, hearing of this, hastily grabbed his corpse and so inherited the property. The present tomb follows a drawing by Rogers in Carrington's "Dartmoor: A Descriptive Poem", opposite page 160. and is topped out by a cross cut in the 1880s; it is in line with others marking the monks' path.

Today only a few courses of Foxtor Farm stand above ground level. When Page wrote his Exploration, published in 1889, he remarked on a barking dog that came out of the house; yet when The Western Morning News collected Crossing's stories in One Hundred Years, 1901, there were only ruins left. The site today is a pile of stones, with walls only a few courses high: apart from nettles and soft rush there is not much else to show that there was a a farmhouse here. Those who lived here needed to be hardy and a story of one such is told. A traveller begged for shelter from the rain, and discovered to his dismay that the roof was leaking badly. He enquired of his host when it would be repaired, but was told that no thatching was ever carried out in wet weather. Once the storm was over, he again asked, only to be told that as it was now dry, the roof clearly wasn't leaking and therefore didn't need any repair.

Further up the Swincombe on the opposite side is a place in altogether better condition, one that gives a clearer impression of how an Improver's homestead might once have looked. There is a small farmhouse with some barns around it. All were very strongly made of granite, for its builder, John Bishop, worked well with stone. Active in the middle 19th century, he was an expert drystone waller who was both well-known and liked. The House was once was two storeys high, all under a fine slate roof, see Worth's plate 83, opposite his page 413. It has so far escaped the attentions visited on other ruins near Burrator Reservoir, which have been ruthlessly reduced down to their foundations.

His house can be reached via Hexworthy: walk along the Sherberton road and turn next left on the Water Authority slip-road, crossing the Swincombe on foot by a clam called Fairy Bridge. An unmade lane enters the field enclosures ; it is part of a route that crossed the Moors to Tavistock, before the present Ashburton to Two Bridges road was made. Walking along it in the early spring, when these photographs were taken, gave a good idea of what all of Devon's bye-ways must have been like before the turnpikes came. There were many difficult stretches of mud and puddles, with water running over loose stones in between: long winter journeys must have proven extremely tiresome.

MINING ON THE SWINCOMBE

The relics of tin mining on Dartmoor tell a story of three phases. Each one had its own boom period, starting with the early Mediaeval streamworking of alluvial deposits. When these were finally exhausted the mother lodes were located and long opencast gullies, or "gerts" like those at Ringleshutes, were dug by pick and shovel. Eventually some were deep enough for ground water to become a problem; they had to be drained by horizontal tunnels - "adits" - dug beneath them and proper, deep mining had at last begun. Finally, in an Industrial Revolution revival, blasting powder made more lodes accessible, gully sides steeper and pits deeper underground. Each phase is well represented here along the Swincombe.

There is an early blowing house next to The Boiler (a name that is not recorded by OS; it refers to the adjacent rapids on the River Swincombe). "Blowing house" is the delightfully onomatopoeic name given to mine buildings equipped with water-driven bellows, which literally blew air into the smelt. There are quite a number all over Dartmoor. Some of the best preserved lie as far apart as Black Tor on the Meavy, on the Avon at Henglake, or on the O Brook near its confluence with West Dart. They are of indeterminate age, using techniques that were little changed between Elizabethan and Regency years. The number 1753 has been scratched on the inside wall here, though it may be no more than an old graffito.

Further upstream on the flat valley floor are walled up shafts that have a much more certain history: they belong to an Industrial Age re-working of an earlier mine around the River Strane, called Whiteworks, because of the colour of the ore produced. In its heyday this was a large undertaking; various shafts and the ruins of both workers houses and other mine buildings lie near to the end of the lane that reaches down from Princetown. Some cottages are the only complete buildings left of this once thriving community.

Below them and on Swincombe's flat valley floor is Foxtor Mire, one of Dartmoor's proper bogs. When Conan Doyle came here he called it Grimpen in one of his Sherlock Holmes stories; the coachman who drove him round was Mr Henry Baskerville, who then worked for the Ashburton hotel where Conan Doyle was staying. Today the area is much less forbidding as mining operations have partially drained it. However there is still a certain unremitting wetness that will snare the unwary, making this a place best left alone.

ABBOT'S WAY

OS marks the Abbot's Way as leaving Huntingdon Cross, going roughly west for Red Lake, but as noted earlier it is most likely a wool trader's path. Along its line lies Erme Pits, which at some time has been mined for tin in a way unique on Dartmoor. There are no gerts here, but a series of deep holes and high, cone-shaped mounds bear witness to the tinners' labour. A prodigious amount of rock has been moved by pick and shovel; the huge pebble-and-gravel spoil heaps left behind are all well-drained and much burrowed by rabbits.

There are plenty here and one dry summer evening they were all out browsing what little green was left. When we approached they fled into the only nearby cover that was still standing above ground, some soft rushes, bottom left. Fortunately for them the dog is the only canine I know to have been actually head-butted by a buck rabbit. It inconsiderately charged him down one day and I do not think his hunting instinct ever properly recovered.

Beyond the Pits, at Broad Rock (SX618672), the trader's path divides. One branch goes directly west towards Plym Steps, which alas are no more (Steps are large, flat-topped boulders, often laid one adventurous step apart across the stream). Another path turns north norwest round Great Gnats Head, bound for Plym Ford. This is the one that OS call Abbot's Way; once across the river they send it north, uphill into a flat and featureless expanse of wet and tiring walking, between the heights of Stream and Crane Hills. Once whilst walking there on a dull and drizzly day, I found no trace of any track and having lost all sense of direction finally descended much too far east, well away from the mapped route to Childe's Tomb and Nun's Cross.

It would have been easier on reaching the Plym to turn downstream, crossing it at the next right-bank tributary and then heading west. This latter place is Hooper's Valley and it has been extensively mined; near its foot is a stamping mill, soft rushes now covering the dressing floor beside it. Following the tinners' gerts that go uphill and north-west eventually leads to a well-used track which runs over Eylesbarrow: this latter reaches the OS Abbot's Way at Nun's Cross.

STALL MOOR CIRCLE

Some stone rows of remarkable length are grouped around the Erme valley. The longest of all starts at a cairn on Green Hill and rambles on for over two miles. At the southern end is a circle on Stall Moor called The Dancers, because some sinners were supposedly caught dancing a sabbat and were naturally turned to stone. There is a central mound, but it is very difficult to see, being barely more than a foot high. No record exists of any excavation, and Butler reports in his Dartmoor Atlas of Antiquities Vol IV, page 75, that the centre is still intact. The circle itself is unrestored and a large number of stones are still upright, though many are so short they barely show above the coarse moor grass.

From the circle there is a fine view south, down the River Erme towards Piles Hill, but dominating the background is the long, keel-like ridge of Staldon. On its summit and clearly visible from the retaining circle is a Bronze Age cairn which much later and quite astonishingly became an eight-day clock factory. In the midst of the cairn is a small ruin, which the story says was built by the clockmaker, whose name was Hillson.

The site can be reached from Watercombe Gate, SX625611, walking directly uphill in a north-easterly direction. After a short distance there is a fine, restored stone row with a truly megalithic northern end; its stones are tall enough to be clearly visible from the circle, which stands on a flattish spur overlooking both the Erme and Blatchford Bottom, about a mile and a half away. It is mostly downhill from the row, with much slow walking amongst the heather.

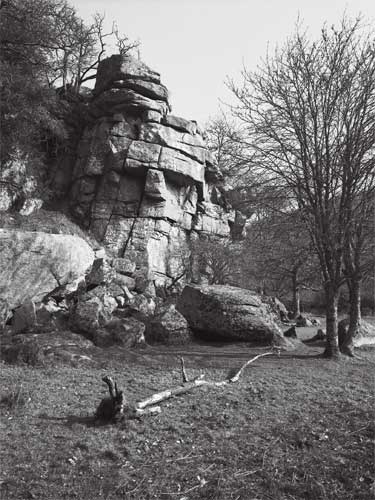

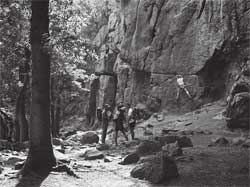

DEWERSTONE WOODS

From Shaugh Bridge a good track leads east, upstream along the River Plym, to a nearby granite riverside cliff known as the Dewerstone, through oak woods that are as beautiful as any in the National Park. Legend has it that this is where the Devil, locally known as Dewer, dispatches those whose souls he enslaves. After having lured them on by riding across the moors with his "Wish" hounds, he disappears over the cliff edge, leaving them to fall onto the boulders below. Today the rock is much visited by climbers.

Upstream there is a path of sorts beside the river: often very narrow, it is in places so badly eroded as to be impassable to all but the adventurous. Nor are detours round such places an easy undertaking, for underneath the trees there is a familiar landscape of steep slopes covered in a moss-covered, root-encrusted scree of large granite boulders. Clambering around them is no light afternoon stroll, but this stretch of the Plym is a delight to see. Here the river cascades through a tunnel made of overhanging boughs in a landscape that swirls and dances with all the contortions of a Van Gogh painting, full of riverbed shapes hammered out by banks of pebbles constantly churned around by every flood.

Mercifully there is an easier alternative route: starting at Cadover Bridge - SX 555647 - a good path follows the left bank downstream. In a little while North Wood is reached; mainly oak it has open grassland beneath the canopy and a picturesque view of the river with its pools below. There is an abandoned clay pipeline above the riverbank, now used as a convenient through route. Walking along it gives glimpses of the Dewerstone itself, until a large concrete-block holding tank is reached ; then the path turns sharply down through the trees, leading on to disused works that are directly above Shaugh Bridge. The pipe carried china clay in suspension for settling and drying in large open circular tanks, which today contain Rhododendron ponticum and Leycesteria, another garden escape that has pretty purple fruits in autumn.

A return can be made by following the right bank's granite roadway, going back uphill and taking the left-hand branch where it forks, away from the Dewerstone. It is a steep uphill climb, past a quarry cut into the hillside. In a while this roadway has holes for taking rails and at the top is something that looks like a wheelpit, but was really made to take a brake drum. On reaching it turn immediately uphill and once through the trees there is a magnificent view of Plymouth, Cornwall from St Austell to Bodmin, and the top of the Dewerstone with its Neolithic camp. North is Brent Tor and Black Down, Cox, Staple and Great Mis Tors; then finally Peek Hill and Lether Tor. Walk north east, keeping the enclosure walls right, and in a little way Cadover Cross will be reached, which is within sight of the car park. Only the cross' head is original: it was found by troops on manoeuvres in 1873. This picture shows it cemented to a modern shaft. Taken in early autumn, drought and hard equinoctial winds had stripped the hedgerow trees of all their leaves.

Warrener's house, Ditsworthy, stands further along the Plym above Cadover. Ditsworthy was one of the three largest rabbit farms upon the Moor. It included burys as far apart as Eylesbarrow and Hen Tor, an area well over a thousand acres in extent. Today the warren house is like Nun's Cross, its windows firmly shuttered against all intrusion. One memorable feature is a very old and gnarled Cotoneaster, a survivor of its garden.

Hen Tor Stack: it takes a bit of imagination to make a hen out of this formation! It stands amongst clitter, the shattered remains of perhaps more jointed formations that once must have made an impressive pile below the long ridge that separates the valleys of the Plym and Yealm.

LEE MOOR

No account of Dartmoor should be made without some reference to one of Devon's major earners: kaolin or china clay. It is a by-product of decomposed granite and there are deep deposits of this soft, crumbly stuff around Lee Moor, between the Plym and Torycombe valleys. The clay is extracted by washing it out of the ground, using high-pressure water cannons, controlled from small cabins that look exactly like white sentry boxes.

Kaolin itself is nearly white, with mica and other crystal waste sparkling when it reflects sunlight, so the exposed clay beds look like very dirty snow. After more than a century and a half of industry, this landscape of pits and tips sits uneasily among the green pastures of south-western Dartmoor, but it does bring a prosperity that agriculture alone could not provide. Unhappily the area is also rich in archaeological remains. One stone row has been covered by a spoil tip in the last few decades. There are others on the moorland above, together with reaves, cairns, pounds and hut circles.

There are a small number of single Bronze Age standing stones placed throughout the National Park. Sometimes called "menhirs", they are not all obviously part of any contemporary megalithic monument. Each of them is flat-sided and carefully selected, so that from one direction they resemble broad pillars, whilst from another they look like thin columns. One such is on the hillside southwest of Trowlesworthy Tor, easily reached from car parks on the Plym above Cadover Bridge. It is called the Leaning Rock because of its appreciable tilt, measured by Hansford Worth as 38° from vertical. Its broad face and relatively low height is a striking contrast to the tall skinny pillar of Beardown Man.

Grazing round about when this picture was taken were some of Dartmoor's ponies. The pure Dartmoor is said to have descended from horses used by the Celts to pull their war chariots. Once upon a time they were all a uniform colour: but some Shetland stallions were introduced to make them smaller for work down northern coal pits. The many party-coloured open moorland ponies seen at the end of the twentieth century are a result of this cross-breeding, which some say is perhaps not quite as hardy.

Stud book records for Dartmoors began in 1899, when much Hackney as well as other blood was present. This mixture was legitimized in a 1901 ruling which stated that all foundation stock should be three-quarters pony blood, with Hackneys restricted to one-eighth. However, some ponies of unknown provenance were still allowed, but this ceased in 1957; nevertheless, the genetic pool of present-day Dartmoors remained small. So small that in 1988 the Dartmoor Pony Society Moor Scheme was started, one aim being the controlled introduction of some much-needed unregistered blood.

The present standard for Dartmoors is 12.2 hands high (a "hand" being four inches) in bay, brown, black, grey, chestnut or roan. Piebald and skewbald are specifically proscribed; while white markings on heads and legs must be small.

There are still pedigree Dartmoors, though they are not as often seen on the open moorland as Shetland crosses. These last are traditionally rounded up in autumn drifts and sold at auction, but their market has had mixed fortunes over recent years. The animal rights movement has successfully campaigned against live exports to the continent. No doubt they considered this a worthwhile cause, but removing livestock markets leaves the animals concerned with an uncertain future, which has not been helped by politicians. Animal passports are being imposed, with pony breeders being forced to pay the bill.

BURRATOR RESERVOIR

This reservoir was built in the Meavy valley between Leather Tor and Sheeps Tor by Plymouth Corporation. It first opened in 1896; some years later in 1916 the city also purchased the surrounding water catchment area and began terminating the leases of all its new tenant farmers. In 1921 conifer planting started and in 1926 the dam was heightened. Its present capacity is just over 1000 million gallons, flooding 153 acres to a maximum depth of 77 feet.

On its southwestern side the long, rocky prominence of Sheeps Tor rises above plantation trees; at its southern end is Pixies House, which is a cave difficult to spot because of obscuring boulders. Tradition has it that a loyal Royalist, one of the Elfords who at the time were a prominent local family, hid in it from Roundheads who were chasing him during the Civil War.

Poised above the water on the opposite side, Lether-OS Leather-Tor has everything typical of Dartmoor. The main rock-pile stands above a ridge that gathers in the contours as it dips to south and east. Here steep slopes are covered in an extensive field of scree. On Dartmoor such boulder fields are known as "clitter" - some older books may call it clatter - and geologists suppose that they result from rocks mechanically split through frost, then thaw, in a cycle repeated many times perhaps during the last ice age. There are no paths here and walking across any part is difficult: not all the boulders are stable and some can rock alarmingly. In addition, lower down the slope everything is hidden all summer under bracken that is in places nearly waist high, which makes navigation especially tricky. However there is a rock-free route to the summit from the road between Yelverton to Princetown, where next to Sharpitor there are car parks and Lether Tor is but a short walk away.

This waterfall is an ignominious end for the Devonport Leat. From the West Dart opposite Wistman's Wood, through beautiful scenery by way of Cowsic and Blackbrook; then through a tunnel between Swincombe and Newleycombe Lake; past Crazywell Pool and some crosses, on down a launder, over an aqueduct and finally, this scruffy pipe beside the road ends it all. Whoever thought up this one had serious iron in his or her soul!

Today Burrator is a popular area and the reservoir itself is heavily visited, much to the frustration of various official bodies. In 1994 the Park Authority had in mind a "traffic management strategy" which would have restricted parking and would also have closed the reservoir ring road.1 This met with such fierce local opposition that it was hastily dropped, though not entirely, for bureaucrats always wriggle when told what they must do; thus the 'right' has been retained to introduce various aspects, at some future, carefully unspecified date. Their plans would have routed all traffic to the reservoir through Dousland, a move seen as "environmental" - except to the residents of that town, who would have suffered all the motor exhaust and other fumes!

PRINCETOWN TRAMWAY

Just like the quarries at Hey Tor, those at Swelltor and Foggintor were connected to the rest of Devon by a railway. The line was proposed by Sir Thomas Tyrwhitt, who in his prospectus gave an extremely optimistic list of freight it might carry. He felt Princetown would import the usual building materials, beer and groceries. It would export, besides granite, such things as flax, oil-cake and potatoes, all crops that the Improvers were enthusiastically experimenting with at the time. His Plymouth and Dartmoor Railway, which in reality was a packhorse tramway, had no initial difficulties signing up eager shareholders, but the costs soon escalated.

After raising an initial tranche of £27,783, work was started in 1819 by Hugh Mackintosh and Bailey and Co, from London. They were supervised by a local engineer, Mr William Stuart. The original plan ended the tramway at Crabtree, then some way short of Plymouth. However, there were problems with the route and it was soon found necessary first to extend the line to Sutton Pool, and next to avoid some impossibly steep gradients by tunnelling through a hill at Leigham. A further £12,200 was raised in two separate amounts, with Sir Thomas and Sir Masseh Lopes being major subscribers, the latter leasing quarry rights on his manor lands at Swell Tor and elsewhere.

Only part of the line had opened by 1823; it was still incomplete two years later and new contractors, Johnson and Brice, who had the lease of Swelltor quarry, were commissioned to finish the work. There was also a new engineer, Mr Roger Hopkins replacing Mr Stuart. Walking back down the track from Princetown, where there is a car park near the site of the old terminus, gives a good idea of the inclines those engineers faced. Just around the first hillside, the line at Yes Tor Brook is directly overlooked: it is only half a mile away as the crow flies, but over 250 feet lower down. To negotiate the slope a detour of 2 miles had to be made round King Tor.

Even after it was fully opened in 1827 the tramway was never an unbridled financial success; some years later the company was bought out and the track turned into a standard gauge railway branch-line. Most of the packhorse route was re-used for trains, but in a few places it was bypassed and its original route can still be followed, such as at Yes Tor Brook. Sadly the steam railway had no more profitable a career than had its predecessor; it closed in 1956, a worthy victim of a certain Dr Beeching. Today the line can be used as a convenient path where it traverses open moorland.

WESTERN QUARRIES

Until the horse-drawn tramway provided a transport system capable of handling heavy loads, none of the quarries on the Moor's western edge were worked on any significant scale. When at last a part of Princetown tramway opened in 1823, operations began in earnest at Swelltor quarry, where there are the ruins of a building beside the railhead loading area. Of all the quarries along the line-others were at Foggin, King and Ingra Tors-this was the last to close. Beside its disused railway siding some wooden sleepers are still in place, now bleached and etched into weathered ridges that barely rise above the close cropped turf. Beside them are completed pieces of carved stone, including surplus corbels for Old London Bridge, now in America, and a bollard intended for Plymouth docks. The stonemasons who made them were not paid by the hour, but only for each piece they completed successfully.

Further along the railway line at Foggintor, quarry operations were substantial enough to warrant building not only offices, but also cottages, a day school and chapel, all just beside its canyon-like quarry entrance. Little of them now remains except their ground-plans: one of the last walls of any height belongs to the manager's house. Granite was worked here for nearly a century and the deepest pit is now permanently flooded. In the middle of winter I once watched a party of Royal Marines practise their climbing skills on one of the quarry faces; when finished they stripped off for a swim, but did not stay too long in the water.

Foggintor granite was sent all over the country, one notable example being Trafalgar Square, where it provides Nelson with his Column. The last moorland quarry to be worked full-time was at Merivale, which shows as a darker mass beneath the Staple tors to the north-west. It provided the stone for the Falklands' War Memorial and was latterly run by Tarmac, who finally made it part-time at the close of 1997, ending nearly two centuries of full-time quarrying on the moors.

The loading area of Swelltor has remains of the railway sleepers still showing above ground. Further uphill, around the stonemasons' workplaces are chippings piled high in waste stone dumps, one of which, aside, is reminiscent of a natural tor.

MERIVALE

Merivale - OS insist on an extra r - has one of Dartmoor's best known Bronze Age collections. There are two double and other stone rows, a longstone, circle and many burials, all on a flat spur of Long Ash Hill, south of the moorland road to Tavistock. Except for the longstone of over ten feet and a kistvaen whose coverstone has been split in two, most of the stones used are rather small. The best way to see them is in snow, when they show up well in black and white, despite their small sizes. Shown here is the southern double row. Rushes to its right mark a pot-water leat that separates this row from the smaller, northern double. That anything remains is remarkable, for the old Ashburton-Tavistock track ran near the site's eastern edge, on its way between the clapper over the Walkham at Merivale and Foggin Tor. Somewhere hereabouts was the potato market of 1625; there was then plague in Tavistock and its people came to buy what food local farmers left for them. They met no-one face-to-face, leaving their money under nearby running water to remove the taint of disease. Some guide books say the actual place was amongst the Merivale antiquities, others place it on the other side of the road, beside some hut circles. The original was told by Mrs Bray in 1836. It is interesting to note that the line of the present road follows that of the turnpike, made well after 1772, which itself lies north of the older Ashburton track over Long Ash Hill, which would have been used in the C17.

Across the Walkham stands a tor which, from the fieldwalls just west of the antiquities, looks insignificant. The rock outcrops of Vixen Tor are all enclosed in a newtake. The vertical stacks have typical jointing that, with their less pronounced horizontal divisions, are similar in style to that of Great Hound Tor. Samuel Rowe, after commenting that from a certain angle Vixen looked like the Egyptian Sphinx, described it with reference to his own especial Druid Theory. He considered the druids enjoyed a hyperborean idyll and had their priests ever worshipped rocks, then this tor would have certainly featured in their ceremonies. Rowe might expect that his views on the supernatural would carry not inconsiderable weight ; when his book was first published in 1848 he was Vicar of Crediton. Lately there has been controversy concerning access-with barbed wire, warning notices and mass trespass. A new owner has closed it after 30 years of public access, which is a pity. The area can be quickly reached from car parks on Barn Hill, SX531752, then walking south-east from them across Whitchurch Common, for about a mile on easy, short turf.

This picture of Vixen was photographed in early summer, just as the Hawthorn blossom was at its best. Some call these bushes May, which must be a misnomer, for all the ones around that year had obdurately flowered in June. The picture itself however, like the name of May, is something of a cheat: for at less than 1000 feet Vixen is actually lower than the surrounding tors and hills. The most imposing view is from the side of Heckwood Tor, which is the camera point, for here there is at 90 feet the tallest free-standing natural rock pile on Dartmoor.

Merivale from Long Ash hill:on the horizon behind the quarry are mid and great Staple Tors. The modern road is carried on an embankment across the walkham, made from local stone. The older road is beside it, complete with its own bridge, just below the right-hand barn.